We used punctuation as part of a prompt in 2012 that featured a poem by Thomas Lux - see poetsonline.org/archive/arch_punctuation.html

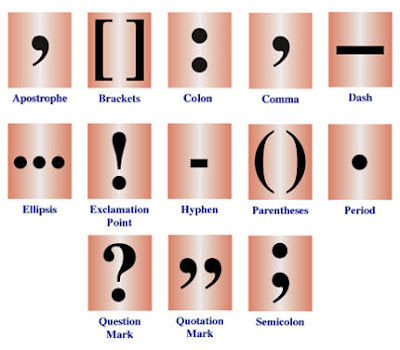

PUNCTUATION: Some poets use it. Some don't.

Of course, there are many poems where punctuation is most definitely necessary, but there are also cases where it is not. Are there any "rules" for its usage?

Students have asked about when they should use punctuation - or should they use it or do they have to use it?

When lines are short - three words or less - punctuation (commas and periods) can look silly.

“Cut out all these exclamation points. An exclamation point is like laughing at your own joke,”

When lines are short - three words or less - punctuation (commas and periods) can look silly.

“Cut out all these exclamation points. An exclamation point is like laughing at your own joke,”

wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald may not have been a fan of the exclamation point, but the New York School of poets took a liking to it.

- Walt Whitman liked... the ellipsis.

- Emily Dickinson was fond of using - the dash.

- A.R. Ammons did things with: the colon.

- E.E. Cummings, besides his experiments with Upper and LOWER case, liked to make use of (parentheses).

From the Poets.org Guide to Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems (pdf download)

"E. E." Dickinson and E.E. Cummings may have more in common in this regard than you would expect. Cummings made his use of punctuation so much of a style that it may seem to be a parody at times. This poem about a grasshopper has just about everything happening in it.

and E.E. Cummings may have more in common in this regard than you would expect. Cummings made his use of punctuation so much of a style that it may seem to be a parody at times. This poem about a grasshopper has just about everything happening in it.

He uses words, punctuation, and space to create a "concrete" visual image of a grasshopper jumping. The word and letter jumble makes more sense as we dig deeper and yet some of it is for pure visual rather than reader effect.

I have used some of his poems with children who like finding a hidden poem. They find the jumping-all-about grasshopper r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r who as we look up now gathering to leap leaps arriving...

They realize the poem is not just meant to be "read."

And then, there's the ampersand. & Not really punctuation, but an abbreviation of a sort. As I have written on another blog:.

A typical manuscript for a poem might include several undated versions, with varying capitalization throughout, sometimes a "C" or an "S" that seems to be somewhere between lowercase and capital, and no degree of logic in the capitalization. While important subject words and the symbols that correspond to them are often capitalized, often (but not always) a metrically stressed word will be capitalized as well, even if it has little or no relevance in comparison to the rest of the words in the poem. Early editors removed all capitals but the first of the line, or tried to apply editorial logic to their usage. For example, poem 632 is now commonly punctuated as follows:

The Brain – is wider than the Sky –

For – put them side by side –

The one the other will contain

With ease – and You – beside –

The Brain is deeper than the sea –

For – hold them – Blue to Blue –

The one the other will absorb –

As Sponges – Buckets – do –

The Brain is just the weight of God –

For – Heft them – Pound for Pound –

And they will differ – if they do –

As Syllable from Sound –

"E. E." Dickinson

r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r

who

a)s w(e loo)k

upnowgath

PPEGORHRASS

eringint(o-

aThe):l

eA

!p:

S a

(r

rIvInG .gRrEaPsPhOs)

to

rea(be)rran(com)gi(e)ngly

,grasshopper;

He uses words, punctuation, and space to create a "concrete" visual image of a grasshopper jumping. The word and letter jumble makes more sense as we dig deeper and yet some of it is for pure visual rather than reader effect.

I have used some of his poems with children who like finding a hidden poem. They find the jumping-all-about grasshopper r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r who as we look up now gathering to leap leaps arriving...

They realize the poem is not just meant to be "read."

And then, there's the ampersand. & Not really punctuation, but an abbreviation of a sort. As I have written on another blog:.

The ampersand is a curious thing in our language that dates back to the 1st century A.D.The & picked up traction in poetry with the Beats and the Black Mountain poets. (Ginsberg: "blond & naked angel") and e.e. cummings, Frank O'Hara, Amiri Baraka, John Berryman, and Nick Flynn.

Originally, it was a ligature of the letters E and T. What's a ligature? In writing and typography, a ligature occurs where two or more graphemes are joined as a single glyph. Ligatures usually replace consecutive characters sharing common components.

Suffice it to say, the ampersand is the most common one we use in English.

"Et" is Latin for "and" - as in et cetera, which is such a mouthful that we feel the need to shorten even that to etc. It can actually be further shortened as &c.